When a coral "bleaches", it expels the tiny, symbiotic algae called Symbiodinium that live in its tissues. Because these algae photosynthesize to provide corals with nutrition, it is harmful and often fatal for corals to lose them. However, corals can recover their symbionts within a period of weeks to months if thermal stress ceases (Jones and Yellowlees 1997; Cunning et al. 2016).

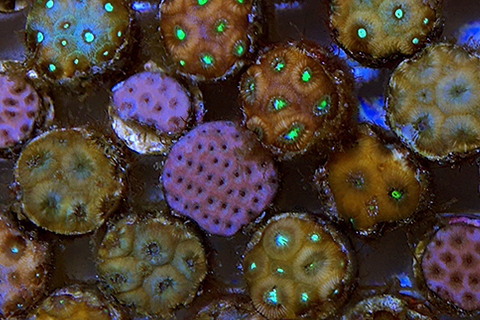

By expelling and regaining Symbiodinium, bleaching and recovery may enable shifts in symbiont community composition (Buddemeier and Fautin 1993). Referred to as ‘symbiont shuffling’ (Baker 2003), this process may modify the relative abundance of different, functionally diverse symbiont types within the host, which may also alter the holobiont phenotype. For example, studies have found that many bleached corals recover with Symbiodinium trenchii (a member of clade D, often referred to as D1a) as the dominant symbiont. S. trenchii has shown more thermal tolerance than other symbiont types, making the host more resistant to future heat stress and increasing the bleaching threshold by ~1-2°C (Berkelmans and van Oppen 2006; Silverstein et al. 2015; Cunning et al. 2015).

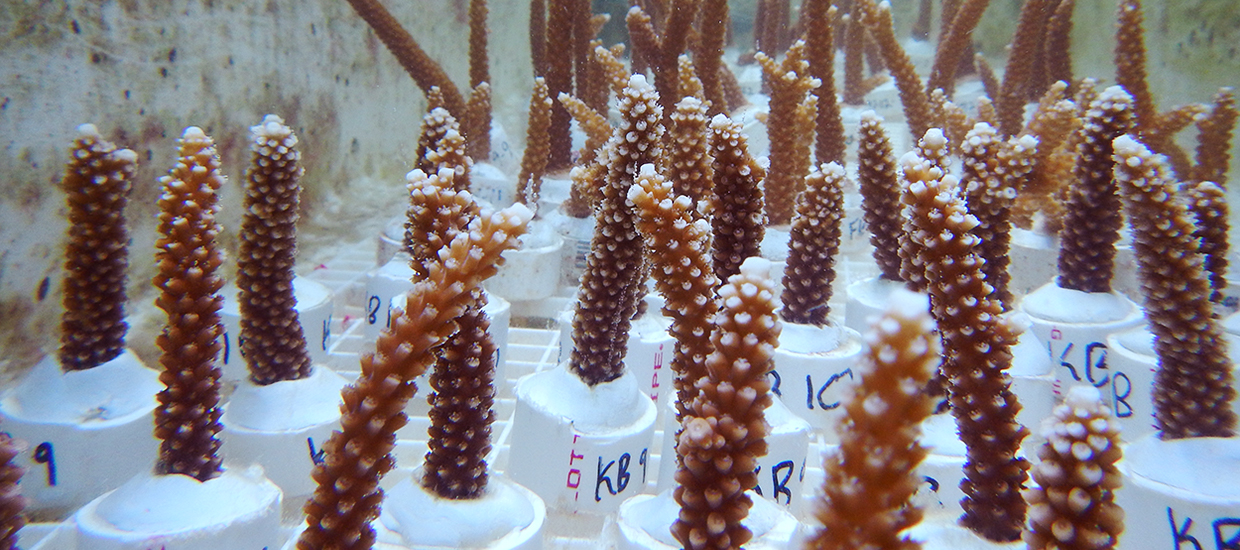

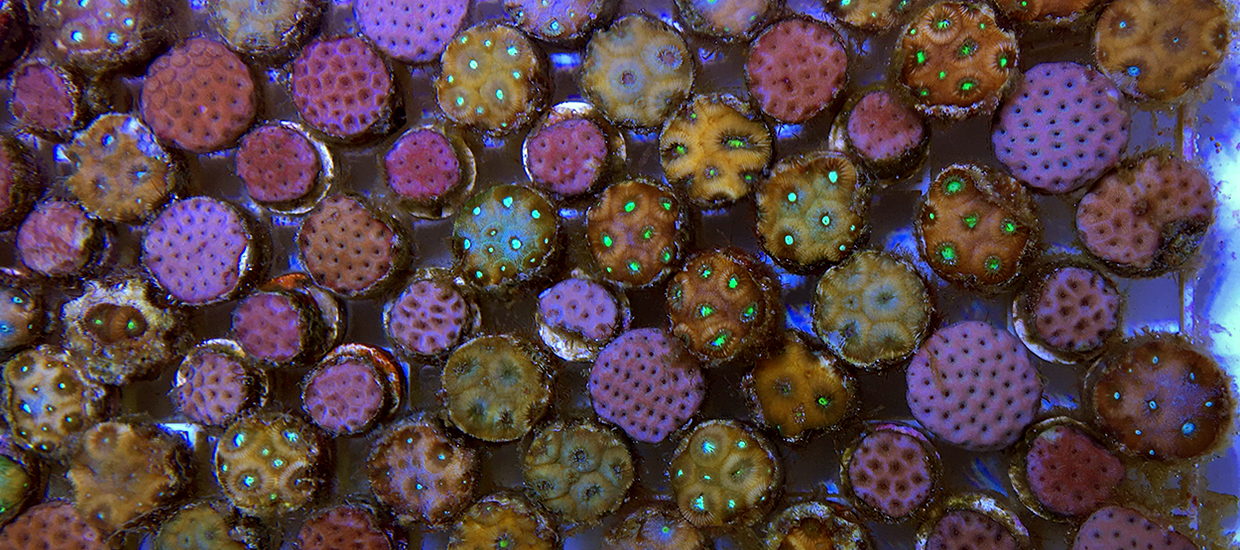

Symbiont shuffling, particularly shifting towards dominance of S. trenchii, may allow corals to rapidly acclimatization when faced with environmental stress, and may help them become more resilient under climate change. The Baker Lab at the University of Miami has achieved this "stress-hardening" technique with many key Caribbean coral species in the lab, and is currently investigating methods for in situ holobiont manipulation. Our hope is that this method may allow managers to prime corals for future climate change and protect against future heat stress.